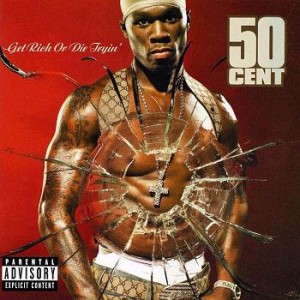

By Jose Antonio PhD FISSN. I’ve been asked so much about CrossFit that I figured I’d share my fiddy cents worth. Now  mind you, naysayers have suggested to me that “if you haven’t tried CrossFit, then you shouldn’t criticize it.” Huh? So let me use that sterling logic. If I can’t run a 9.9 sec 100 meter dash, then I can’t comment on sprinting. If I haven’t actually finished a marathon in 2 hr 30 min or less, then I can’t comment on that either. So only those who climb Mt Everest have an understanding of altitude physiology? And if you want to compete in the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, then I guess only dogs can comment on that. Those pre-conceived notions make about as much sense as fighting Mike Tyson with two arms tied behind your back.

mind you, naysayers have suggested to me that “if you haven’t tried CrossFit, then you shouldn’t criticize it.” Huh? So let me use that sterling logic. If I can’t run a 9.9 sec 100 meter dash, then I can’t comment on sprinting. If I haven’t actually finished a marathon in 2 hr 30 min or less, then I can’t comment on that either. So only those who climb Mt Everest have an understanding of altitude physiology? And if you want to compete in the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, then I guess only dogs can comment on that. Those pre-conceived notions make about as much sense as fighting Mike Tyson with two arms tied behind your back.

News Flash: if you understand the underlying physiology and biochemistry of any exercise or sport (i.e., overload, specificity, progression, etc), then you should be able to provide sound and evidence-based advice. It’s called SCIENCE.

Moving on.

What is there to love or perhaps not love about CrossFit?

I do like the fact that folks who do CrossFit love it. It has rekindled a passion to exercise and to look forward to the next workout or WOD. I mean they just can’t wait to see the WOD of the day! That’s the kind of excitement that you might see when a Parisian runway model looks forward to her dinner of bread sticks and cheese. So any reason to get your fat butt off the couch and move a little is a good thing. Heck, some people love yoga; downward dog to your heart’s content; some love climbing mountains even though folks DIE each year attempting to climb Mt Everest. Me. I’d rather be outside and on the water. So what’s the deal with CrossFit? Here’s some data. It does improve various parameters of fitness.

Scientists studied the effects of a Crossfit-based high intensity power training (HIPT) program on aerobic fitness and body composition. They took healthy men (23 subjects) and women (20 subjects) spanning all levels of aerobic fitness and body composition and had them do 10 weeks of HIPT. Their workouts consisted of lifts such as the squat, deadlift, clean, snatch, and overhead press which were performed as quickly as possible. Additionally, this program included skill work for the improvement of traditional Olympic lifts and selected gymnastic exercises. After ten weeks of training, they showed significant gains in maximal oxygen uptake in both men and women. Also, % body fat dropped in both men (before: 22.2%, after: 18.0%) and women (before: 26.6%, after: 23.2%). These science eggheads concluded that “our data shows that HIPT significantly improves VO2max and body composition in subjects of both genders (sexes) across all levels of fitness (Smith, Sommer, Starkoff, & Devor, 2013).

Moral of that story: If you train like this for 10 weeks, you’ll lose fat, gain LBM and get in better aerobic shape. Nothing new there.  However, the ‘problem’ with CrossFit (and I am using the classic definition of it) is that there is no conceptual framework for program design, progression, or specificity (i.e. motor unit recruitment or energy systems). Folks who claim that CrossFit is the best way to get in ‘shape’ have no idea what that means. There is no such thing as getting in ‘shape.’ Being in shape for what? Running a 10k in 30 minutes or less? Competitive powerlifting? Bodybuilding? Playing lacrosse? Running a 4.4 sec 40-yd dash? Hitting a baseball? Playing shortstop? A pitcher? A goalie in hockey? Doing the high jump, triple jump, or long jump?

However, the ‘problem’ with CrossFit (and I am using the classic definition of it) is that there is no conceptual framework for program design, progression, or specificity (i.e. motor unit recruitment or energy systems). Folks who claim that CrossFit is the best way to get in ‘shape’ have no idea what that means. There is no such thing as getting in ‘shape.’ Being in shape for what? Running a 10k in 30 minutes or less? Competitive powerlifting? Bodybuilding? Playing lacrosse? Running a 4.4 sec 40-yd dash? Hitting a baseball? Playing shortstop? A pitcher? A goalie in hockey? Doing the high jump, triple jump, or long jump?

Any first year exercise science college major understands the underlying principle of ‘specificity’ such that training must be tailored to the goals of the athlete or individual. CrossFit is what I call the REG – random exercise generator. For instance, a cursory look at a CrossFit website had the following WOD (workout of the day).

Three rounds of time of:

- Run 200 meters

- 100 meter walking lunge

- 50 squats

Another had the following. Three rounds for time of:

- 30 Wall ball shots, 20 pound ball

- 75 pound Sumo deadlift high-pull, 30 reps

- 30 Box jump, 20″ box

- 75 pound Push press, 30 reps

- Row 30 calories

- 30 Push-ups

- Body weight Back squat, 10 reps

If you’re wondering WTH, then go to the head of the class. These workouts make absolutely no sense if your goal is to train for a specific athletic event. It would be like asking a sumo wrestler for weight loss advice. Also, you should know that the primary energy system used in CrossFit based workouts is fast glycolysis or the lactic acid system. Much of how CrossFit is implemented is just a variation of interval training (which some call HIIT). Interval training is NOT NEW. You can go back 70 years ago and find that famed distance runner, Emil Zatopek, was one of the first to utilize the interval training method. Whether it involves sprint repeats on a track or doing a series of weight-training (or in CrossFit’s case, Olympic-style lifts) exercises with little rest period, it is still a form of interval training. Funny how folks think CrossFit is a new way of training.

Now just because I beat up on the conceptual framework (or actually lack thereof) of CrossFit doesn’t mean you should quit if that’s what you like to do. Exercising is a laudable activity regardless of the reason. If love CrossFit, stick to it. If you like doing triathlons, by all means enjoy it. If you like lifting weights, have a frickin’ party. However, don’t be fooled into thinking that CrossFit is best way to train for everyone. Any program that claims to be the best for everyone is basically the best for no one. Unless you incorporate principles of overload, progression and specificity properly and correctly, then all you have is the REG – random exercise generator. If you want to improve your general overall fitness, choose CrossFit. On the other hand, if you want to excel in an actual competitive sport (e.g., powerlifting, track and field, baseball, softball, combat sports, football, lacrosse, hockey, badminton, volleyball, swimming, triathlons, distance running, tennis, squash, racketball, x-country skiiing, downhill skiiing, canoeing, kayaking, stand-up paddling, the decathlon, golf, gymnastics, mountain biking, rugby, sailing, table tennis etc.), then I’d suggest you work with a qualified strength and conditioning professional who knows the basic principles of exercise training.

Reference

Smith, M. M., Sommer, A. J., Starkoff, B. E., & Devor, S. T. (2013). Crossfit-based high intensity power training improves maximal aerobic fitness and body composition. J Strength Cond Res. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318289e59f